First black mayor, Fatburger founder: These are some snapshots from L.A.’s black history

Black History Month tends to focus on national figures of change, like Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. and Rosa Parks. Less is known about the African American civil rights pioneers who have made a difference in Southern California.

Los Angeles — a mosaic of distinct communities and cultures — has had its share:

The founders of the First African American Methodist Church downtown in 1872. An L.A. resident who in 1918 became the first known African American in the West to hold statewide office. The black workers who built the canals of Venice but were not allowed to live in the beach town. The woman who founded a burger stand that remains popular today.

This Black History Month, we highlight a portion of that story, some of the black Angelenos and cultural centers that make up our shared history. It is a mere snapshot.

A continuing conversation about Los Angeles through its people and places can be found at latimes.com/WeAreLA

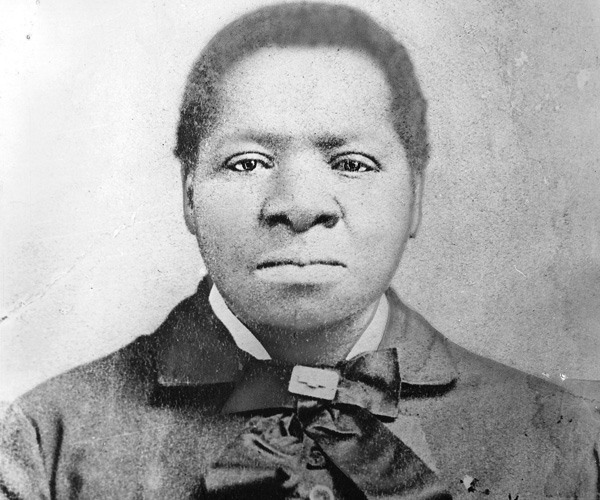

Bridget ‘Biddy’ Mason: From slavery to entrepreneur

Born a slave in 1818, Biddy Mason walked to California from Mississippi behind her master’s wagon.

After meeting freed slaves in San Bernardino, she went to court and won her freedom in 1856. For the next 10 years, she saved her wages from jobs as a midwife and nurse to buy property near 4th and Spring streets in downtown L.A.

In the years that followed, “Biddy Mason’s Place” became known as a daycare center and orphanage. Then in 1872, with 11 other people, Mason founded the First African Methodist Episcopal Church of Los Angeles in her home. The first actual church building was constructed at 4th Street and Grand Avenue on a plot also owned by Mason. In the 1880s, she also financed a disaster center for residents left homeless by flooding.

Mason died in 1891 at 72 years old.

An 8- by 81-foot timeline memorial of Los Angeles’ and Mason’s intertwined history was erected in 1989 on a parking garage wall at 333 S. Spring St., near where her home once stood.

— Tre’vell Anderson

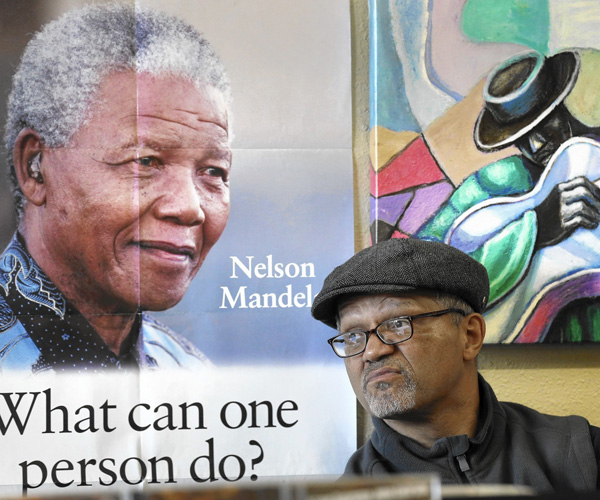

Tom Bradley: L.A.’s first black mayor

All his life, Tom Bradley had to fight.

Even though he had graduated near the top of his police academy class and gone on to become Los Angeles’ first black mayor, Bradley faced constant criticism. And when it came, he had a swift comeback:

“I’m not a black this or a black that. I’m just Tom Bradley.”

In 1940 he was sworn, one of 100 black officers on the LAPD’s 4,000-member force. In an interview years later, he discussed the limited opportunities back then for black officers:

“When I came on the department, there were literally two assignments,” Bradley once told a Times reporter. “You either worked Newton Street Division, which has a predominantly black community, or you worked traffic downtown… . You could not work with a white officer, and that continued until 1964.”

After leaving the force, Bradley went to law school and became active in politics. He joined the Crenshaw Democratic Club, a multi-ethnic group with the California Democratic Council, and later became the club’s president. The choice alienated local black leaders, who supported Jesse M. Unruh.

In 1963, Bradley was the first black elected to the Los Angeles City Council. Representing the Crenshaw district, he was a tough LAPD critic — citing the department’s handling of the 1965 Watts riots and segregation within the police force.

In 1969, he ran for the mayor but lost to conservative Sam Yorty, who portrayed Bradley as a black militant. He ran for mayor again in 1973 and won.

A supporter of business and community policing, Bradley served until 1993.

—Jerome Campbell

El Pueblo de Los Angeles State Historic Park

Los Angeles’ first black community was within the first pueblo here. In February 1781, 44 people set out from Spanish Colonial Mexico to establish a pueblo between the missions in San Gabriel and Santa Barbara. More than half of them—26—were of African descent. Their ancestors were some of the estimated 100,000 to 200,000 Africans brought to New Spain by the Spanish as slaves and laborers in the 1500s and 1600s. By 1700, most were free subjects of New Spain, integrated with the local Indian tribes and mestizo population, and helped to colonize Alta (North) California.

A plaque near the gazebo in El Pueblo de Los Angeles pays tribute to those 11 families that arrived here Sept. 4, 1781, and lists their names, age and race.

African American Firefighter Museum

Fire Station No. 30 was one of only two stations in the city where African Americans were allowed to work during the first half of the century. After the U.S. Supreme Court declared “separate but equal” public schools unconstitutional in 1954, other public agencies, including the Fire Department, were forced to desegregate. The black firefighters, whose numbers had been limited by the fact that they could only work at two stations, were spread throughout the city, often only one to a station.

In December 1997, Fire Station No. 30 was turned into a museum honoring those men and their predecessors in the department.

Bronzeville

The area of downtown L.A. known as Little Tokyo was in the 1940s briefly transformed into a black enclave called Bronzeville.

Before the start of World War II, 30,000 Japanese and Japanese Americans lived in the 3-square-mile neighborhood. After the attack on Pearl Harbor and the declaration of war against Japan, the residents along Central Avenue were among those taken from their homes and forced into camps like Manzanar.

As Little Tokyo emptied, property owners actively planned to create a “Latin American quarter” after the war. Instead blacks — many of whom had come from the Deep South in search of work — moved in. Most of Los Angeles had racially restrictive housing covenants, barring people of color from living in white neighborhoods.

Soon jazz clubs opened in the area. The most famous was Shepp’s Playhouse Club, where saxophonist Charlie Parker held court. It quickly became a hot spot for celebrities like Judy Garland, Joe Louis, Count Basie and Gene Kelly. The Civic Hotel, on the corner of 1st and San Pedro streets, housed the Lionel Hampton Band. That was where Parker — in a drug-induced stupor, according to news reports at the time — walked through the lobby wearing nothing but a pair of socks. He was trying to get change to make a phone call.

In 1943, The Times wrote that “Los Angeles’ increasing Negro population in the E. First St. area has formed a ‘Bronzeville Chamber of Commerce,’” noting that signs were displayed on buildings and in store windows that read, “This is Bronzeville. Watch Us Grow!”

After the war ended, Little Tokyo’s displaced residents returned, and the residents of Bronzeville eventually scattered to other areas of Los Angeles.

Of Little Tokyo’s Bronze age, newsstand owner James Hodge said this in the book “Little Tokyo: One Hundred Years in Pictures” — “The sun never went down in this neighborhood. Guys were spending money with both hands. It was real exciting … but it only lasted about three years.”

— Michelle Maltais

Sugar Hill/West Adams district

Starting in the 1930s, the West Adams district was home to many of Los Angeles’ middle- and upper-class African Americans. Among the Hollywood set who lived there were actresses Louise Beavers, Butterfly McQueen and Oscar winner Hattie McDaniel.

The neighborhood had been predominantly white until the Depression, when many residents were forced to sell their homes. In an effort to keep blacks out, restrictive covenants were attached to property deeds, forbidding blacks to own or inhabit homes there. In 1943, a group of white homeowners actually tried to remove about 30 black families from the neighborhood, including the three famed actresses of the day. But such covenants—which covered huge portions of the city—were deemed unenforceable by the U.S. Supreme Court in 1948 and outlawed completely five years later. A few years after that, Sugar Hill—as West Adams was also known—was unceremoniously split in half by the Santa Monica Freeway construction.

Golden State Mutual Life Insurance Co.

The Golden State Mutual Life Insurance building is as significant for the business inside as is the structure itself. In 1925, William Nickerson Jr., Norman O. Houston and George A. Beavers started an insurance company in a few upstairs rooms in an office building along Central Avenue. Their clients were African Americans, who were forced to pay punitively high premiums by other, white-owned companies, or deemed uninsurable altogether.

The large, modern building at Western Avenue and Adams Boulevard is testimony to their success. Noted black architect Paul Revere Williams—who also designed the Hollywood YMCA, Chasen’s restaurant and numerous stars’ homes—designed the building.

Golden State Mutual had a nearly unrivaled collection of African American art, including works by painters Charles White, Barnette Honeywood and Hughie Lee-Smith and painter-sculptor Elizabeth Catlett. Two large murals from 1949 by Hale Woodruff and Charles Alston depict the history of blacks in California.

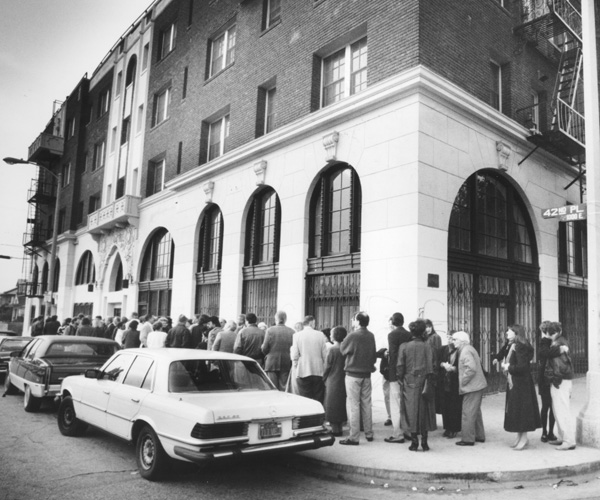

Jewel’s Catch One: a place to meet — and dance — for the black LGBT community

In sequined dresses and leather jackets, afro puffs and high-top fades, they lined up outside the stucco nightclub on Pico Boulevard off Crenshaw, sometimes wrapping around the block. Once inside, they danced under strobe lights and a lone disco ball. Celebrities would make pit stops when they were in town — from Madonna and Sharon Stone to “Queen of Disco” Sylvester. As the sun rose, they left drenched in euphoria and sweat.

But the joy experienced at Jewel’s Catch One nightclub was more than a weekend choice for fun; it was an act of defiance by black lesbian, gay, bisexual and transgender people in the face of clubs in West Hollywood, where they felt unwanted because of their race.

Jewel Thais-Williams, 76, opened “The Catch” in 1973 to provide a safe space where black LGBT folks could enjoy themselves in one another’s company. Decades later, the Catch would be the last black-owned gay club in Los Angeles.

But the nightly crowds dwindled to just a handful, and the club closed in 2015.

—Tre’vell Anderson

Nat King Cole: Standing his ground in Hancock Park

It was just another mansion in Hancock Park. Until the summer of 1948, when 401 Muirfield Road became a flashpoint in a civil rights battle.

Famed musician Nat King Cole bought the home, once owned by the president of the Los Angeles Chamber of Commerce, for $65,000. It took a while for white residents to find out the real owners because, they alleged, Cole had bought the home through a “dummy” purchaser to get around the property rules that restricted blacks from owning in the upscale neighborhood.

Residents protested, but Cole stood his ground.

He was not alone. Other prominent blacks — including Hattie McDaniel, the first African American to win an Oscar — had to fight to live in Los Angeles neighborhoods with racial restrictions.

– Shelby Grad

Eso Won Books: Where the black experience is chronicled and cultivated

Anthony Graham stood before the cash register at Eso Won Books in Leimert Park, weighing his thirst for knowledge against the funds in his bank account.

The $27.99 price tag for “Black Against Empire: The History and Politics of the Black Panther Party” gave him pause. Graham was also considering another book on the same subject, “The Shade of the Panther.”

“It’s bad, but not horrible,” said book store co-owner James Fugate, giving the book a firm thumbs down. “The author gets the fact straight, but doesn’t understand how the Panthers worked and how (FBI director J. Edgar) Hoover systemically tried to take them down.”

As Graham kept mulling over the higher price of the first book, Thomas Hamilton, Fugate’s business partner, interjected.

“It’s not how much it will cost you,” he said, sitting on a stool, his arms folded in front of his chest. “But how much will it cost you if you don’t get it?”

At Eso Won Books, Los Angeles’ venerable African American bookstore, customers come for hard-to-find literature that chronicles the black experience, but many keep coming back for the Siskel & Ebert-like reviews from the two shop owners.

“You can’t get that from Barnes and Nobles,” said Graham, 30, of Gardena. Fugate’s “knowledge guides me and the services are unparallel.”

Fugate and Hamilton are opposites in many ways: Fugate, 61, is tall and thin, quick-witted and opinionated. Hamilton, 62, is shorter and athletic, with a common sense, meat-and-potatoes style.

More than just book store owners, the pair are like museum curators, stewards to a collection that celebrates black culture and identity. Comic books with black superheroes, children’s books with little girls in cornrows, and fairytales with black boys — their skin unapologetically dark, their noses broad — grace the shelves.

“I can walk into a place like this and see books for me and by people like me,” said Beverly Haynes, 56, of West Adams. “This grounds me and molds me as a black woman.”

The bookstore carries classics from James Baldwin, W.E.B DuBois and Zora Neale Hurston, as well as the latest autobiographies and books on race relations.

In the era when big chains stores and small independents have folded due to competition from Amazon and e-books, Eso Won Books has survived by catering to black Los Angeles.

“We buy the books we think that people should have,” Fugate said.

The store has hosted book signings for former president Bill Clinton, poet Maya Angelou and a freshman senator from Illinois named Barack Obama.

In more recent years, Eso Won has been a cultural center for a black community jolted by the killings of Trayvon Martin, Michael Brown and Ezell Ford. They’ve come looking for answers to why things happen — from within the pages of Francis Cress-Welsing’s “The Isis Paper,” a book about symbolism, racism and white supremacy and Michelle Alexander’s “The New Jim Crow.”

Last year’s best-seller was Ta-Nehisi Coates’ “Between the World and Me.”

“Everybody in my generation thought that the battle was won,” Fugate said. “But you read these books and you see we’re fighting some of the same battles we thought we settled 50 years ago.”

Eso Won Books has weathered financial turmoil and failed business deals that promised expansion. The store has outlived dozens of black-owned niche bookstores that sprung up in the late 1980s and early 1990s to become the only such shop in Los Angeles.

Beginning with Fugate and Hamilton selling books out of the back of their car, Eso Won has changed locations several times in its 28 years. But in the last decade, it has nestled into a home in Leimert Park Village.

The book store has remained a constant, even as change has surrounded it.

Construction clogs the Crenshaw corridor as crews build the new rail line that will stop in Leimert Park. Hipsters stroll the village, long considered the epicenter of L.A.’s African American art and culture. Rents continue to rise, sparking fears that the subway station will alter the quaint quarters of the village.

On a recent Saturday, a dozen people listened as a panel discussed the lack of diversity in cinema. The sound of steel drums floated through the glass doors as customers moved in and out. As the crowd grew, Fugate went in the back to grab additional chairs. Three women, two white and one Asian, slid into the seats.

The event ended with the sounds of jazz filling the cozy space. Karen Farmer of Leimert Park and two friends visiting from Oakland and Atlanta thumbed through the books. One of the women pulled Nigerian novelist Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie’s newest, “We Should All Be Feminist,” from the top shelf.

The three women huddled together and discussed her last work, “Americanah.” Farmer said she cherishes her time at the bookstore and was excited to share it with her friends.

“It’s a tactile experience — picking up books, touching it, listening to the wonderful jazz,” she said. “This is for us.”

Back at the counter, Graham decided to buy the “The Isis Paper” and left. But Hamilton’s message stuck in his brain: Don’t let the price deprive you of the knowledge.

Two days later he returned to purchase “Black Against Empire.”

—Angel Jennings

Melina Abdullah: Keeping the spirit of activism alive

“If we hope to bring about change, we have to take care of our people. But ‘our people’ isn’t just a concept. They are our families and neighbors.”

For two decades, Melina Abdullah has pushed herself to live up to those words — her own.

Now a professor of Pan-African studies at Cal State L.A., she moved here to pursue a doctorate in political science at USC and wound up integrating herself into the fabric of the city. For that she credits her late mentor and professor, Michael Preston.

“He encouraged me to engage with people as human beings,” Abullah said, “connecting concepts to their experience.”

She spent five years at L.A. Youth at Work, a Chamber of Commerce initiative that prepares disadvantaged kids for the workforce. That job, she said, helped her find and understand the black Los Angeles experience.

It also helped her form relationships with the city’s politicians and community organizers.

Those connections would be called upon in July of 2013, when George Zimmerman was acquitted in the killing of Trayvon Martin. The day the verdict was announced, Abdullah and hundreds of others met in Leimert Park to protest.

Three days later a fellow activist — Patrisse Cullors — called Abdullah and others to St. Elmo’s Village, where the group organized the first chapter of the Black Lives Matter movement. There now are 35 chapters across the globe.

“The movement has called black people to fiercely love ourselves,” Abdullah said. “We have seen black people rise up, and people have begun to take notice.”

That pride, and civic activism as a way of life, is something she is passing on to her three children.

“My children are built into the movement. They come to every meeting and they get love from lots of other people,” Abdullah said. “It allows me and other mothers to be a part of the movement in a way that does not sacrifice our lives.”

—Jerome Campbell

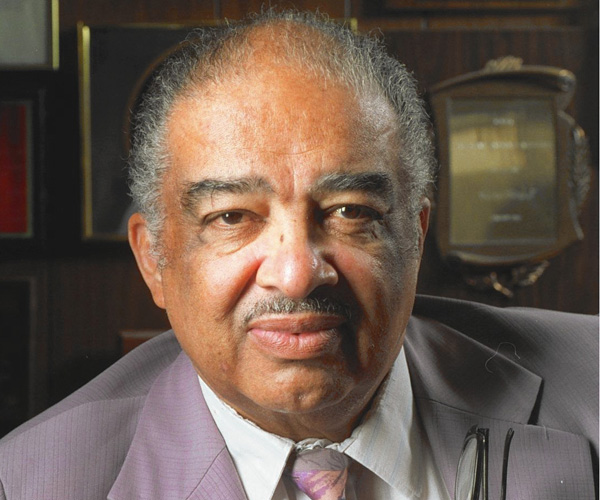

Celes King III: L.A. civil rights leader

If you spend any time in South L.A., you’ve likely seen Celes King III’s name.

At the corner of Crenshaw and Martin Luther King boulevards, there’s a sculpture of him gazing down. At the end of MLK and Rodeo Road, his name graces the indoor swimming facilities at Rancho Cienega Recreation Center.

A vocal activist and founding state chairman of the Congress of Racial Equality, King had served as an officer in the all-black Tuskegee Airmen during World War II., but because of racial discrimination, never saw combat.

As a staunch Republican, his views often were in conflict with those of black political leaders, including the late Los Angeles Mayor Tom Bradley. He was among the few blacks on the California Central Republican Committee.

King also was instrumental in renaming Martin Luther King Jr. Boulevard (once known as Santa Barbara Avenue) in South Los Angeles. That tribute to the famed civil rights leader, he said, was “an important cosmetic reminder for generations to come.”

Celes King died at age 79 in 2003.

— Michelle Maltais

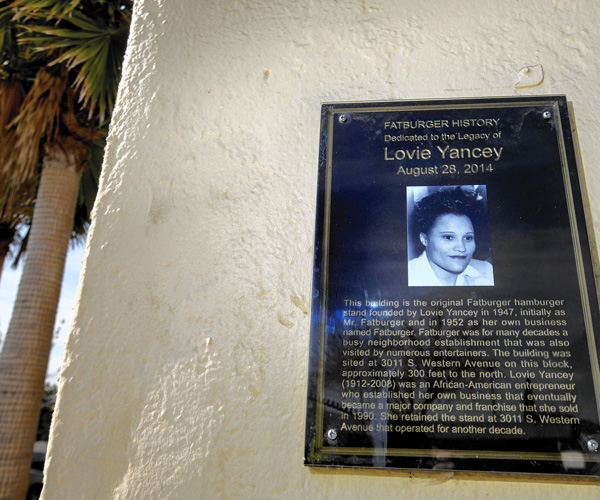

Fatburger: From South L.A. hamburger joint to franchise

Before Ronald, Wendy and the Burger King, there was Mr. Fatburger.

Founded by Lovie Yancey in 1947, the fast food chain started out as a three-stool stand on Western Avenue near Jefferson Boulevard in South Los Angeles.

The establishment became known for its massive, custom burgers and attracted celebrities like Ray Charles and Redd Foxx. (Others — including Pharrell, Kanye West, Montel Williams and Queen Latifah — now own their own Fatburger franchises.)

Over the years, “The Last Great Hamburger Stand” was immortalized in a string of TV shows, movies and songs, including “Sanford and Son,” “The Fast and the Furious” and Ice Cube’s single “It Was a Good Day.” Fatburger even once made David Letterman’s Top 10 list for things he’d miss most about leaving Los Angeles.

“I don’t worry about McDonald’s, Burger King or Wendy’s,” she told the Wave in 1985. “They may be more popular, but a good hamburger sells itself, and I don’t think anybody makes as good a hamburger as we do.”

Yancey sold her Fatburger company to an investment group in 1990, but retained control of the original property on Western Avenue. It was sold in 2007 with the requirement that it could never be torn down.

Yancey, who was born in Texas, died in 2008 at 96 years old. The original Fatburger stands today, incorporated into a housing development.

—Tre’vell Anderson

The Lincoln Theatre

Starting in the 1920s, the Lincoln Theatre was the preeminent venue for African American entertainment in the West. Theater productions, swing music, movies and comedians all performed in the building, which today houses Iglesia de Jesucristo Judá.

The California Eagle

Under editor Charlotta Bass, the California Eagle crusaded for voting rights and the end of Jim Crow laws, covered the lives of African Americans largely ignored by the other daily newspapers and exposed the plans of the Ku Klux Klan. After the Eagle reported in 1925 that the KKK was trying to influence the government of Watts, which had not yet been incorporated into Los Angeles, the Klan sued for libel. After losing, eight Klansmen tried to intimidate Bass at her office one night. They retreated after she pulled a gun out of her desk. Today that two-story brick building holds a furniture store.

Bass, who came to Los Angeles in 1910, practiced what her weekly paper preached. She took over the Advocate, renaming it the California Eagle, in 1912 and the paper lasted until 1964. She was a labor activist and after she sold the newspaper in 1951, she ran for Congress and later for vice president on the Progressive Party ticket.

Ralph Bunche House

Years before he was a diplomat and Nobel laureate, Ralph Bunche was a student at John Adams Junior High School and Jefferson High School. The small frame house is where Bunche lived with his family until he graduated from UCLA in 1927.

Bunche taught political science at Howard University from 1928 to 1940 and earned his doctorate from Harvard in 1934. He later went to work for the State Department and then the United Nations, advising members on issues related to African colonialism. In 1950, his efforts as part of the U.N. Palestine Commission earned him the Nobel Peace Prize, making him the first African American to be so honored.

Dunbar Hotel

In the 1920s, John Alexander Somerville, a USC-trained dentist who immigrated from Jamaica, was denied a room at a hotel in San Francisco because he was black. In 1928, he built his own hotel on Central Avenue at 42nd Street, determined to give blacks a high-quality place to stay in Los Angeles.

When the stock market crashed in 1929, Somerville lost the hotel, which was bought by the Lincoln Hotel Co. and renamed after the black poet Paul Laurence Dunbar. Located next door to the now-gone Club Alabam and near other clubs, the Dunbar was the home-away-from-home for countless jazz notables, including Cab Calloway, Duke Ellington and Count Basie. Some of their names are still visible on the directory of residents at the front door. The refurbished building and the block to the south are the most enduring reminders of this corridor a half-century earlier. In the lobby is “Pride and Perseverance,” a display about Central Avenue in its heyday.

Fred Roberts: a civic leader and political pioneer

In 1918, when L.A.’s population was not quite 3% black, a Republican named Frederick Madison Roberts was elected to the California Assembly, becoming the first known African American in the West to hold statewide office.

The newspaper publisher, mortuary owner and community leader represented the 62nd District — including Watts — which at the time was 70% white. During his 16 years in office, Roberts sponsored legislation to establish UCLA, expand the use of school textbooks and institute anti-lynching measures. He was defeated in 1934 by Democrat Augustus F. Hawkins, who also was black.

Roberts moved to Los Angeles with his family from Ohio in 1865, when he was 6 years old. He was the first black graduate of Los Angeles High School and after college took over his father’s business — Los Angeles’ first black mortuary.

He was killed in 1952 in an automobile accident. In 1957, the city of Los Angeles dedicated a park his honor at 48th and Honduras streets in South Los Angeles.

— Michelle Maltais

Watts Towers

Built between 1921 and 1954 by Italian immigrant Simon Rodia, the three spiraling towers became a sort of visual symbol for the community of Watts when they emerged unscathed from the 1965 uprising.

Annexed by Los Angeles in 1926, Watts was the gateway for many of the city’s immigrants, including thousands of African Americans from the South and Texas driven west during the Depression. By 1950, more than 70% of Watts residents were black. Today, the area is more than half Latino.

The Watts Towers Art Center has a gallery, sponsors classes and even has a composer-in-residence. On Feb. 27 the new Cultural Crescent Amphitheater will be dedicated as well.

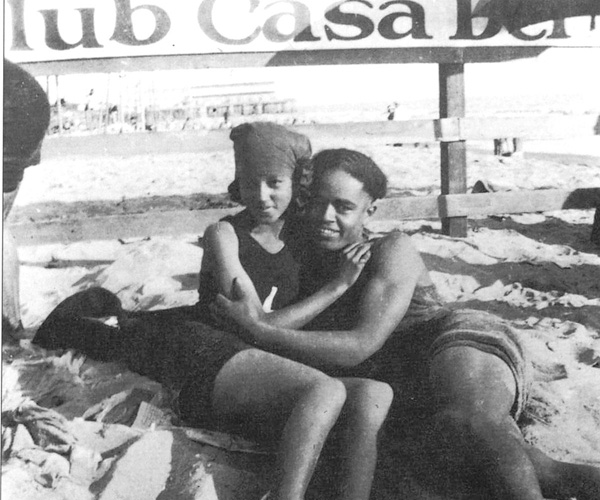

Inkwell Beach: In a ‘Whites Only’ era, an oasis for L.A.’s blacks

Black folks don’t swim – at least that’s how the stereotype went. Former Dodgers executive Al Campanis once claimed it had something to do with buoyancy.

Really it was more about access than ability.

When segregation ruled, blacks were barred from using public pools, mostly located in white neighborhoods. There was limited access to public beaches.

Inkwell Beach was one oasis for black beachgoers in L.A. It’s where Nick Gabaldon, the first documented surfer of black and Mexican descent, practiced taming the waves in the 1940s.

But there’s a story behind how Inkwell Beach came to be:

A young black chauffeur named Arthur Valentine and his family had settled on a section of the “whites only” beach for Santa Monica’s Memorial Day festivities in 1920. When they did not budge after three officers ordered them to leave, one of the cops “tossed aside a small black child who got in their way,” wrote Douglas Flamming in “Bound for Freedom: Black Los Angeles in Jim Crow America.” The police beat Valentine and then shot him.

When Valentine filed a complaint, authorities charged him with assault with a deadly weapon. Historical records do not say he had one.

Over the next three years, Flamming wrote, Valentine was periodically assaulted by police. His lawyer, Los Angeles Dist. Atty. Thomas Lee Woolwine — who filed felony assault charges against the officers, was heckled by Ku Klux Klan members. The charges against both sides eventually were dropped.

The incident prompted blacks to claim their own sliver of public beach near the Crystal Plunge, a former open-air swimming pool that had been destroyed by a flood in 1905, then abandoned. The area was a polluted, debris-filled spot that no one else wanted.

Around 1922, it became known as Inkwell Beach — “inkwell” being an offensive term used by whites to describe areas frequented by the black community. The 200-foot-long roped-off area at the foot of Pico Boulevard was marked “for Negroes only.”

In 2008, Santa Monica installed a plaque on Ocean Front Walk describing the Inkwell as “a place of celebration and pain.”

—Tre’vell Anderson

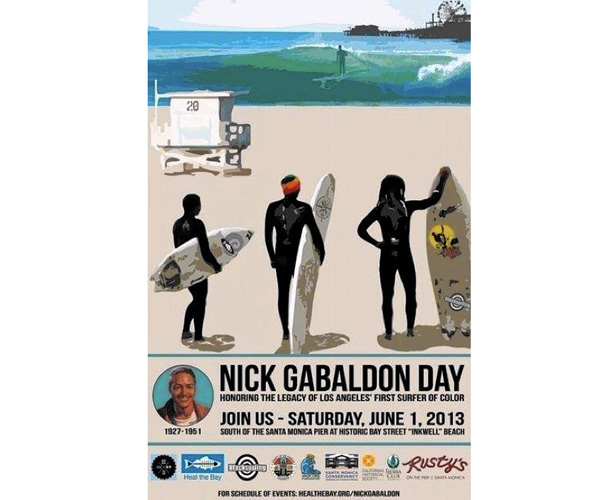

Nick Gabaldon: Surfer made sport more accessible

While many were fighting for equality on land, Nick Gabaldon took the fight offshore.

For Gabaldon, surfing in 1940s Southern California became a political act. At a time when African Americans were not welcome on most public beaches, “the Inkwell” — a slice of sand at the end of Bay Street in Santa Monica — became a gathering spot for many, including Gabaldon.

The first documented black surfer in California (he was actually half-Latino), Gabaldon never joined the professional ranks. Self-taught, he would paddle 12-miles to Malibu to challenge himself on larger waves.

“And because he was good at surfing,” said Alison Rose Jefferson, a historian of black Angeleno history, “he overcame with many people … He was making a contestation by being in these identified white spaces.”

Gabaldon died in a surfing accident in Malibu in 1951. He was 24.

In 2008, the city of Santa Monica dedicated a plaque to the young surfer. The Black Surfers Collective holds an annual remembrance of Gabaldon and offers free surfing classes to many children who otherwise may not have been exposed to the sport.

“That’s why we’re trying to hold up his legacy,” said Damien Baskette, a member of the collective. “I’ve seen kids get hooked right away. You have to show there’s more than just the parking lot around the house.”

—Steve Saldivar

Black Oscars: Honoring black talent in Hollywood

Formally known as the Tree of Life Awards, the Black Oscars was a private event held on the eve of the Academy Awards, where the best in black Hollywood celebrated themselves.

The annual event was launched in 1981 by the late Albert Nellum, a Washington, D.C.-area attorney. It took its name from the ancient African symbol of family, unity and struggle for survival.

“It was always a celebration of what accomplishments black people had done in the film industry,” said actress and director Debbie Allen, who has been honored by the Black Oscars and its sister event, the Black Emmys. “Sound, music, directors, actors, whatever your participation was, you were honored.”

A private group called the Friends of the Black Oscar Nominees ran the ceremony. Those involved in putting on the dinner included Quincy Jones, Sidney Poitier, Maya Angelou, Cicely Tyson and casting agent Reuben Cannon. Black Oscar nominees were invited, along with others whose work had been influential. Winners received black and bronze carved statuettes.

Former honorees and attendees include Denzel Washington, Halle Berry, Will and Jada Pinkett Smith, Ving Rhames, the late Bernie Mac, Queen Latifah, Eddie Murphy and Vivica A. Fox.

The Black Oscars held its last event in 2007.

News reports at the time said that the Friends of the Black Oscar Nominees felt there was no longer a need for a separate event, because black artists had broken through at the Academy Awards. Actors Jennifer Hudson and Forest Whitaker and sound mixer Willie D. Burton would win the coveted gold statue that year.

—Tre’vell Anderson

Ryan Coogler: Filmmaker tackles human-rights violations

Ryan Coogler is the director of the breakout films “Fruitvale Station” and “Creed.” But the big screen isn’t his sole platform.

In 2014, Coogler co-founded Blackout for Human Rights — a network of filmmakers, entertainers, spiritual leaders and everyday people who are pooling their resources to address what they see as human-rights violations in the United States. According to its website, the group is working toward an “immediate end to the brutal treatment and inhumane killings of our loved ones.”

Earlier this year, Blackout organized an event for Martin Luther King Jr. Day, called #MLKNow, at the historic Riverside Church in Harlem, N.Y. The eight-hour program highlighted speeches by civil rights leaders including King, Malcolm X and Sojourner Truth — recited by the likes of “Creed” stars Michael B. Jordan and Tessa Thompson, Oscar-winning actress Octavia Spencer and celebrated entertainer and civil-rights icon Harry Belafonte.

In 2014, the group spearheaded #BlackoutBlackFriday, a national call to boycott Black Friday shopping following the racial unrest in Ferguson, Mo.

Other notable members of Blackout include Ava DuVernay, Jesse Williams, Nate Parker, Joseph Gordon-Levitt and David Oyelowo.

—Tre’vell Anderson