The L.A. Riots: 25 years later

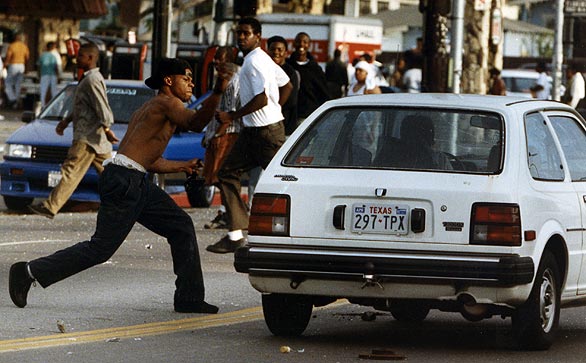

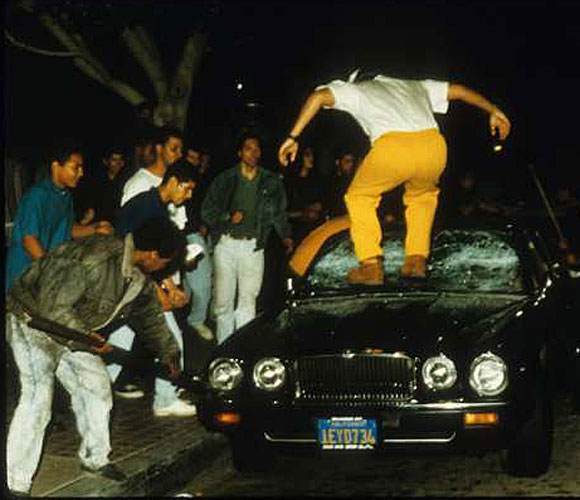

On the afternoon of April 29, 1992, a jury in Ventura County acquitted four LAPD officers of beating Rodney G. King. The incident, caught on amateur videotape, had sparked national debate about police brutality and racial injustice. The verdict stunned Los Angeles, where angry crowds gathered on street corners across the city. The flash point was a single intersection in South L.A., but it was a scene eerily repeated in many parts of the city in the hours that followed.

Not guilty

Sgt. Stacey C. Koon and Officers Laurence M. Powell, Theodore J. Briseno and Timothy E. Wind are acquitted of the March 3, 1991, beating of Rodney G. King. Jurors were not convinced that a 81-second videotape of the incident represented the entire story. The video, filmed by George Holliday, showed officers delivering repeated baton blows and kicks as King rolled on the ground. Its images have been seared into the minds of viewers the world over who have watched the tape broadcast repeatedly.

Florence and Normandie

Police respond to their first report of trouble at the intersection of Florence and Normandie avenues — beer cans being thrown at passing motorists — but quickly retreat and don’t return for almost three hours. The violence escalates and spreads to areas throughout the city.

Parker Center

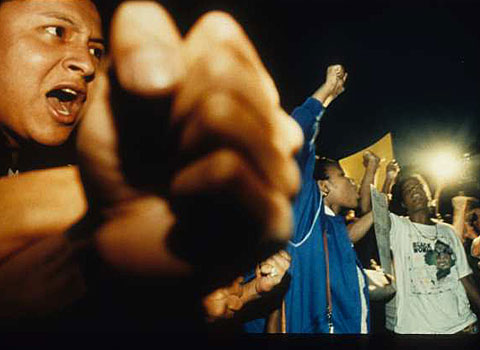

Angry demonstrators begin gathering outside police headquarters and TV stations air scenes of violence near Florence and Normandie avenues. Police Chief Daryl Gates declares his officers are dealing with the situation “calmly, maturely, professionally.” He then drives to a Brentwood reception and fundraiser for the campaign against Charter Amendment F, a police reform ballot measure.

Flash point

Cameras televise gravel truck driver Reginald Denny being dragged from his cab and beaten nearly to death. By this point, the intersection of Florence and Normandie has been the scene of angry protests and violence for more than three hours. Beaten with a tire iron, a fire extinguisher and a brick, Denny is rescued by four strangers — two men and two women — who emerge from the crowd and drive his 18-wheeler to safety.

Gates returns

Daryl Gates, who had left LAPD headquarters hours earlier to attend a fundraiser in Brentwood, returns to the city’s Emergency Response Center between 8:30 and 9 p.m. Gates and Mayor Tom Bradley had not spoken to one another directly for more than a year before the unrest. The chief’s relationship with the City Council and the Police Commission was also strained.

State of emergency

Mayor Tom Bradley calls a local state of emergency. Moments later, Gov. Pete Wilson, at Bradley’s request, orders the National Guard to activate 2,000 reserve soldiers.

A call for calm

Bradley, in a grim televised address shortly after 11 p.m., says the city will “take whatever resources needed” to quell the violence. He says the city is receiving assistance from the county Sheriff’s Department, the California Highway Patrol and police and fire departments from neighboring cities. “We believe that the situation is now simmering down, pretty much under control,” Bradley says. “Stay off the streets. It’s anticipated that a curfew will be put into effect tomorrow night.”

Curfew zone

Bradley declares a sunset-to-sunrise curfew within the area bounded by Vernon Avenue on the north, the city limits on the east, Century Boulevard on the south and Crenshaw Boulevard on the west. The directive also prohibits the sale of ammunition and the sale of gasoline except for automobiles.

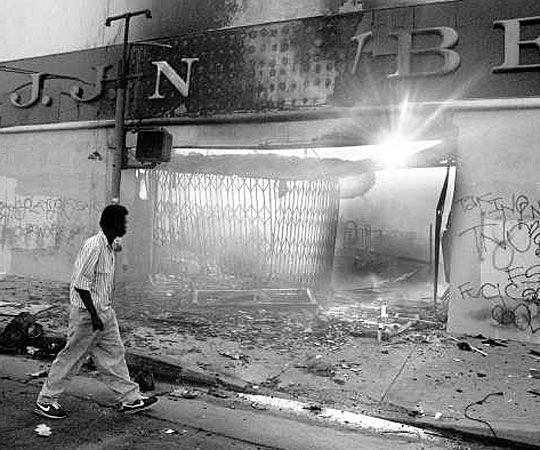

Everyday life shattered

By sunrise, it is clear the riots have disrupted life across a wide path — from downtown to the Westside, from South Los Angeles to Pasadena. By day’s end, bus service is canceled citywide. Many employers tell workers to stay home. Mail delivery is halted throughout South Los Angeles. Professional baseball and basketball games are canceled. Schools are closed throughout L.A.— and in Inglewood, Compton and Lynwood.

Curfew zone expands

Bradley expands the curfew zone to cover more of the area scarred by violence to the area bounded by Jefferson Boulevard on the north, Central Avenue on the east, Century Boulevard on the south and Crenshaw Boulevard on the West. The directive continues to prohibit the sale of ammunition and the sale of gasoline except for automobiles.

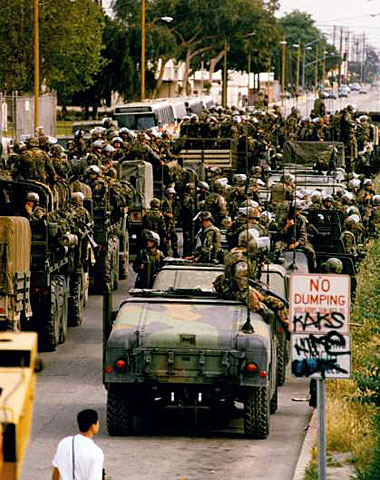

National Guard deployed

Beginning around noon, the National Guard is officially deployed. By late afternoon, hundreds of troops take up positions in hot spots around the city.

Citywide curfew

Bradley declares a citywide curfew. The directive continues to prohibit the sale of ammunition and the sale of gasoline except for automobiles.

More Guard troops

Shortly before midnight, Bradley and Wilson announce they have requested more National Guard troops to bring the Los Angeles County total to 6,000. They also ask the U.S. military to be placed “on alert.”

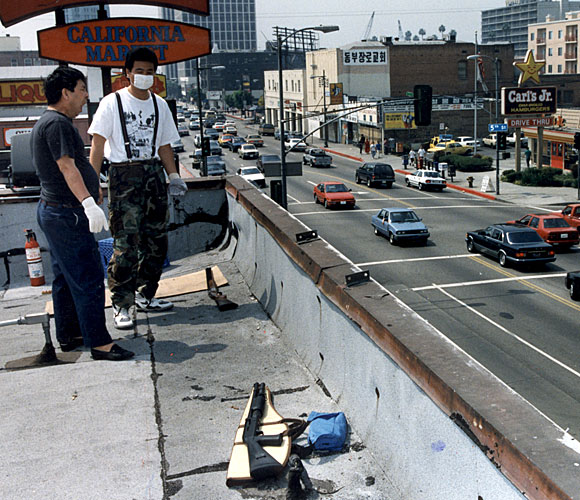

Peace rally in Koreatown

Scores of merchants from South Los Angeles to Mid-Wilshire to Koreatown arm themselves with shotguns and automatic weapons to protect against looters and firebombs. With the city still in turmoil more than a 1,000 Korean-Americans and others gather at a peace really at Western Avenue and Wilshire Boulevard.

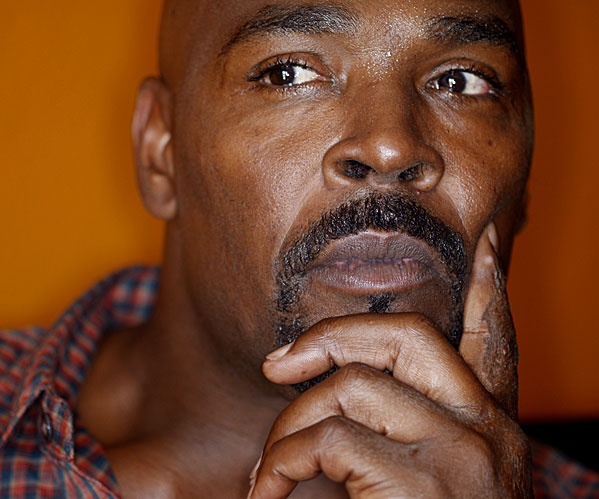

Rodney G. King breaks silence

Outside the office of his Beverly Hills attorney, hundreds of reporters gathered to hear Rodney G. King make a public statement in which he deplored the street riots and urged calm.

Wearing a blue sweater, blue shirt, blue tie and blue slacks, he stepped into the swarm of reporters. Nervous and barely audible, his voice lost at times to the blasting sounds of helicopter rotors overhead, King asked “People, I just want to say … can we all get along? Can we get along?”

More troops arrive

About 4,000 federal troops, Marines and soldiers begin arriving at Marine Corps Air Stations in Tustin and El Toro. By 6 p.m., most of the National Guard troops are deployed.

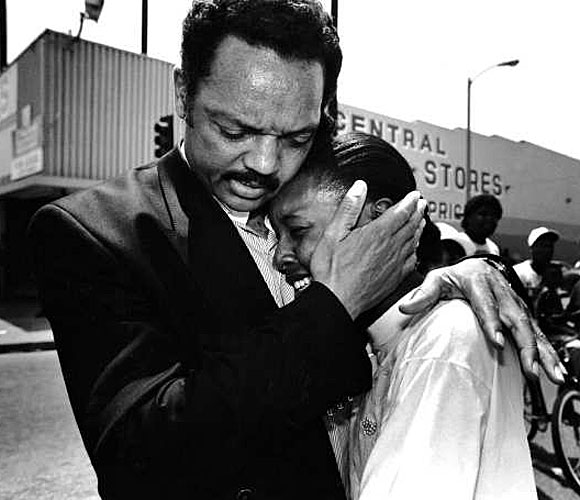

The Rev. Jesse Jackson

The Rev. Jesse Jackson meets with leaders in Koreatown to urge an end to animosity between African American and Korean American communities.

Jackson, who arrived in Los Angeles on Thursday, traversed the city from dawn to midnight pleading for an end to violence and a renewal of hope.

He met with a weary crowd at a post office at 43rd Street and Central Avenue, prayed with victims of the riots at an Inglewood hospital, preached in a predominantly white church in Pasadena and visited Praises of Zion, and many other African American churches.

Habor Freeway off-ramps reopen

The Harbor Freeway off-ramps from Martin Luther King Boulevard to Imperial Highway are reopened. On the first night of the riots, the California Highway Patrol had closed the exit ramps off the Harbor Freeway from the Santa Monica Freeway to Century Boulevard. The closure was later moved south.

Los Angeles returns to work

_opt.jpg)

With their street corners still guarded by rifle-toting soldiers, Los Angeles residents return to work and school.

Thousands queue up at state employment offices. Economists estimate that 20,000 to 40,000 people were put out of work when their places of business were looted or burned.

Probe of police response

Former FBI Director William H. Webster is appointed to direct an investigation of the Los Angeles Police Department’s heavily criticized response to the rioting, looting and violence that swept large areas of the city after the verdicts in the Rodney G. King beating case.

Commission’s findings

The findings of the commission headed by former FBI Director William H. Webster and Police Foundation President Hubert Williams center on a massive failure of LAPD and City Hall leaders to adequately plan for civil disorder prior to verdicts being handed down in the Simi Valley trial of officers accused of beating Rodney G. King.

The investigation was ordered by the city Police Commission after a barrage of criticism that the LAPD’s sluggish response to the violence permitted rioting to spread to wide areas of the county. In all, more than 50 people died and nearly $1 billion in property was damaged.

Damian ‘Football’ Williams convicted

Damian Monroe Williams, convicted of throwing a brick that struck trucker Reginald O. Denny in the head during the opening hours of the Los Angeles riots, is sentenced to 10 years in jail — the maximum term — for that attack and for assaults on four other people at Florence and Normandie avenues.

Koon and Powell guilty

A federal jury returns guilty verdicts against Los Angeles police officers Stacey C. Koon and Laurence M. Powell for violating Rodney G. King’s civil rights. Officers Theodore J. Briseno and Timothy E. Wind are acquitted for their role in the March 3, 1991, arrest and beating.

Koon and Powell sentenced

A federal judge orders Officer Laurence M. Powell and Sgt. Stacey C. Koon to spend 2 1/2 years in prison for violating Rodney G. King’s civil rights, a sentence far less than requested by prosecutors and one that brought the wrenching case to a controversial finale.

Deaths during the L.A. riots

More than 60 people lost their lives amid the looting and fires during the Los Angeles riots that ravaged the city over five days starting April 29, 1992. Ten were shot to death by law enforcement officials.

Forty-four people died in other homicides or incidents tied to the rioting. By year’s end, Los Angeles had 1,096 homicides, a record. 1992 remains L.A.’s deadliest year. The exact number of people who died in the riots is open to debate, but The Times confirmed 63 victims.

Sources: Times research

Credits: Maloy Moore