Timeline Bell: ‘Corruption on Steroids’

The Bell corruption scandal burst onto the nation’s front pages in 2010 as a story about a small city whose leaders paid themselves outsized salaries.

As the scandal unfolded, it became clear that the problems in Bell dated back years and permeated city government. The timeline below tracks key events.

Robert Rizzo sentenced

Four years after he became the face of municipal greed, Robert Rizzo breaks his long silence in a Los Angeles courtroom and asks a judge for mercy.

The former Bell administrator is pale and baggy-eyed, and his thinning hair has turned gray. For many, there was hope that he would finally reveal how he engineered a brazen scheme to boost the salaries of top officials that left the working-class city tumbling toward bankruptcy.

But in a small, halting, scratchy voice, Rizzo offers only the vaguest of apologies, and no details.

“I breached the public’s confidence,” Rizzo tells Los Angeles County Superior Court Judge Kathleen Kennedy. “I am very sorry for that.”

Comparing him to The Godfather, Kennedy sentences Rizzo to 12 years in state prison on corruption charges and orders him to pay nearly $9 million in restitution.

“Mr. Rizzo, you did some very, very bad things for a very long time,” she tells the 60-year-old.

The judge allows him to serve his time concurrently with a 33-month federal prison term he received earlier for income tax fraud. Rizzo could be a free man in six years, with time off for good behavior.

Angela Spaccia sentenced

A Los Angeles County Superior Court judge lashes out at former Bell leader Angela Spaccia, sentencing her to more than 11 years in prison and branding her a “hog” for tapping the town treasury for her lavish salary while the working-class city slid toward insolvency.

Spaccia became the first person sentenced in the municipal corruption case. Kennedy also ordered the 55-year-old to pay more than $8 million in restitution to the city.

As she orders Spaccia to prison, Kennedy — who has spent years sitting in judgment of those involved in the Bell corruption case — calls the former assistant city manager a “con artist” who used the trust of residents as her weapon and never expressed remorse for her crimes.

“It was all about the money,” Kennedy says. “Ms. Spaccia likes to portray herself as somehow a victim of Mr. Rizzo. She is no victim. … She got unbelievable amounts of money.”

Council members plead no contest

The long-running Bell corruption scandal draws toward an end as five former council members plead no contest to criminal charges and agree to pay restitution to the small, cash-strapped city that could approach $1 million.

The pleas end the prosecution of seven officials accused of bilking the city out of more than $10 million that they used for excessive salaries and perks. At one point, council members were receiving up to $100,000 a year for their part-time work, while the city’s top administrator, Robert Rizzo, pulled in $1.5 million annually in total compensation.

Rizzo pleads guilty to tax charges

Robert Rizzo, the former city manager of Bell already pleaded no contest to 69 corruption felonies, pleads guilty to federal tax charges in which he claimed more than $770,000 in phony losses, mostly on his horse ranch.

Rizzo dressed in a blue blazer and gray pants, as he has for nearly all his court appearances. His hair, dyed brown when he was illegally receiving $1.5 million in annual compensation from Bell, is gray.

He agreed in December to plead guilty to one count each of conspiracy to commit tax fraud and making a false income tax return.

Longtime Bell city administrator Robert Rizzo, who became a national symbol for public corruption for alleged graft in the small city, pleads no contest to 69 charges.

Los Angeles County District Attorney Jackie Lacey says in a statement that Rizzo agrees to serve 10 to 12 years in state prison, which she describes as the largest sentence ever in an L.A. County public corruption case.

The Bell corruption trial comes to a chaotic end as the judge declared a mistrial on the outstanding counts, saying “all hell has broken loose” with the deeply divided jury.

An exasperated Los Angeles County Superior Court Judge Kathleen Kennedy draws the case to a close after a bizarre day in which one juror asked to reconsider the guilty verdicts. Kennedy refused.

On the 18th day of deliberations, jurors in the Bell corruption trial have reached a verdict in the case against six former council members accused of misappropriating public funds.

Defendants Luis Artiga, Victor Bello, George Cole, Oscar Hernandez, Teresa Jacobo and George Mirabal, along with their attorneys, are expected to arrive at the downtown Los Angeles criminal courthouse by 10:45 a.m.

The Bell corruption trial begins with prosecutors depicting six former council members as greedy operators who schemed to collect outsized salaries by serving on various government boards that did nothing.

But attorneys for Geore Cole, Victor Bello, Luis Artiga, Oscar Hernandez, Teresa Jacobo and George Mirabal portray them as helpless pawns. They claim former city administrator Robert Rizzo controlled the city and was the mastermind of the alleged corruption.

An attorney for Robert Rizzo, the former city manager of Bell facing corruption charges, says his client cannot get a fair trial in Los Angeles and will seek a change of venue before the trial begins, which could happen this summer.

James Spertus says he doesn’t believe it is “remotely possible” for his client to get a fair hearing in the area served by the Los Angeles Times.

Jennifer Lentz Snyder, assistant head deputy of the district attorney’s Public Integrity Division, says she believes the trial can be heard in Los Angeles County.

A judge rejects an effort by Bell’s former police chief to more than double his pension to $510,000 a year, saying that the City Council never approved his extravagant contract and that city officials tried to keep his salary secret.

Randy Adams, who was fired as the city was engulfed in scandal, would have become one of the highest paid public pensioners in California had his request been approved.

James Ahler, the administrative law judge who heard the case, said that keeping Adams’ contract secret was part of a plan by former City Administrative Officer Robert Rizzo and former assistant administrator Angela Spaccia to hide city salaries.

Already one of California’s highest paid public pensioners, former Bell Police Chief Randy Adams asks a state pension panel to double his retirement pay to reflect the huge salary he received during his brief stint as the top cop in the scandal-plagued city.

If Adams wins his case, which is being heard in Orange County, his pension would zoom to $510,000 a year, making him the second-highest-paid public pensioner in California.

On the witness stand, Adams invokes his 5th Amendment right to not incriminate himself 20 times, including when asked about his Bell salary, which was among the highest law enforcement paychecks in the nation.

Having already dramatically cut the pensions of Bell’s two former top officials, the state retirement system slices their retirement checks further, ruling they are not entitled to five years’ worth of credit they bought for themselves with city funds.

Robert Rizzo, Bell’s former chief administrative officer, and Angela Spaccia, the former assistant chief administrative officer, were sent letters by the California Public Employees’ Retirement System on June 6, notifying them of the decision.

Rizzo’s pension has now been reduced to about $50,000 a year.

Spaccia could have expected a pension of $250,000 annually from CalPERS, along with a huge bump from the Bell program. As it stands, she will now receive a pension of about $34,000.

The state reaches a disciplinary settlement with the accounting firm that failed to detect financial irregularities in Bell despite money problems that pushed the city to the brink of insolvency and led to a public corruption scandal.

Mayer Hoffman McCann must pay a $300,000 fine and as much as $50,000 for the cost of the investigation, according to the settlement with the California Board of Accountancy. In addition, its license is suspended for six months, although that was stayed, meaning the firm can continue practicing in the state while it serves two years’ probation.

“We have taken the events at Bell and the findings … very seriously, and we have used this as an opportunity to renew our commitment to high-quality audit services,” William Hancock, president of Mayer Hoffman McCann, said in a prepared statement.

Bell appoints a new city manager to replace Robert Rizzo, and it’s someone who is no stranger to controversy.

Doug Willmore had been fired as city manager of El Segundo after announcing he had discovered that, for decades, Chevron had paid millions of dollars less in taxes on its refinery in the city than did refineries elsewhere in the state. Willmore said the El Segundo City Council fired him “in retaliation” and that he expected to file a lawsuit against his former employers.

Willmore faces the task of rebuilding Bell, a city with a legacy of mismanagement.

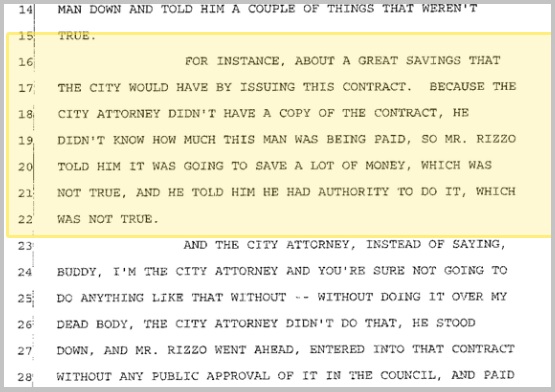

From the day authorities handcuffed and led away eight Bell administrators and politicians in a massive public corruption case, people have wondered why it wasn’t the Bell 9 instead.

Missing in the line-up of defendants was the town’s police chief.

For running the city’s 46-person Police Department, Randy Adams made more than the Los Angeles police chief or the Los Angeles County sheriff. His contract, prosecutors said, was drawn up so citizens would be unable to learn the real size of his paycheck.

At a routine hearing on the Bell case, Superior Court Judge Kathleen Kennedy asked: “I don’t know why he is not a defendant in this case.” Kennedy added later: “That is not a man of integrity. This is not the man who is going to clean up the Police Department.”

A judge forcefully rejects a motion to drop corruption charges against six former Bell City Council members.

In a scathing 10-page ruling, Judge Kathleen Kennedy pushes aside the former council members’ argument that they did not know they might be breaking the law and that their salaries were protected by the city’s charter, which was adopted in a little-noticed election that drew only several hundred voters.

“The city of Bell charter,” Kennedy writes in her ruling, “did not make Bell a sovereign nation not subject to the general penal laws of the State of California.”

The judge, who is scheduled to preside over the trial of the former Bell leaders, said that ignorance is not a defense.

Six former Bell council members ask a Superior Court judge to dismiss corruption charges against them, arguing that voters in the city gave them the authority to draw annual salaries of nearly $100,000, which prosecutors say amounted to thievery.

When just over 300 voters went to the polls in 2005 and approved a little-noticed ballot measure declaring Bell a charter city, it allowed council members to get around state laws that limited how much they could be paid, defense lawyers say.

The argument is part of an effort to get the court to drop criminal charges against the half-dozen former council members, who were arrested in dramatic fashion last year.

The state retirement system slashes the benefits of scores of top-paid local government officials as part of a review of overly generous public pensions prompted by the Bell scandal.

CalPERS also dramatically cuts the pensions of top officials in Bell after an audit determined that they were improperly inflated, according to records obtained by The Times under the California Public Records Act.

Previously, former City Administrator Robert Rizzo had been poised to get $650,000 a year from CalPERS and more than $1 million annually overall when a second pension from the city was included.

The pension of his assistant, Angela Spaccia, is slashed from a projected $250,000 to $43,000.

Grand jury transcripts reveal that $4.5 million is sitting in a special pension fund designed by Rizzo and Spaccia to boost already generous compensation to city employees.

Rizzo tries to funnel $14 million into a second retirement plan for himself and Spaccia, but the city does not have the money, transcripts show. Even after disclosure of his enormous salary, Rizzo calls the city’s finance director and tells her to move money into the account. When she balks, Rizzo tells her, “I’m still the CAO.”

After emergency state legislation allows the county Board of Supervisors to certify the election results, the new City Council is sworn in.

“We are coming in with a clean slate,” says new mayor Ali Saleh (right).

Bell voters head for the polls.

Election posters and lawn signs blanket the city. Voters turn out in droves for candidate forums. “There’s energy here, there’s hope here — look at this place,” candidate Ana Maria Quintana says at one packed community forum.

By the end of the night, there will be more dancing in the streets. Bell voters resoundingly cast out the entire City Council, with more than 95% voting in favor of recalls.

Los Angeles County Superior Court Judge Henry J. Hall (right) orders six current and former Bell City Council members to stand trial on charges of looting the city treasury.

“The allegations are, in my opinion, appalling,” he says. “These people may not be involved in the running of that city in any shape or form.” He orders them to stay away from City Hall, effectively stripping their authority to make decisions.

During two other preliminary hearings, Hall also orders Rizzo and Spaccia to stand trial. He calls Rizzo’s salary “obscene” and Spaccia’s attitude “cavalier” and recommends prosecutors consider filing additional charges.

Preliminary hearings for the “Bell 8” get underway. A judge must decide if there is enough evidence to order them to stand trial.

Bell council members turn down prosecutors’ offer of a two-year sentence, which would have required restitution

Residents are outraged by the offer, says Cristina Garcia, a spokeswoman for BASTA. “Two years isn’t enough,” she says. “The people of Bell are going to be paying for generations for what they have done.”

Pictured left to right: Rizzo, Spaccia, former Councilman Victor Bello and Mayor Oscar Hernandez.

As the city’s legal bills mount — along with the $5.5 million that must be refunded to taxpayers — Bell’s financial woes become a pressing problem.

A county audit finds Bell could have trouble providing basic services by year’s end with a projected $2-million budget shortfall. A report by interim city administrator Pedro Carrillo (right) is even more dire. Bell, he says, is on the brink of insolvency.

Times’ columnist Steve Lopez visits the International Surfing Museum in Huntington Beach where Rizzo (right) is doing security work in the parking lot, community service for his DUI.

Lopez’s column, titled “Robert Rizzo is serving time behind cars,” deeply divides readers.

Lopez responds: “To critics who say I was too harsh or unfair for attempting to interview Robert Rizzo, the reviled former Bell city official who is now guarding a parking lot in Huntington Beach, I’ve carefully considered the criticism …First, I have no regrets. Second, I’m not sorry. I thought it was worth asking Rizzo if he had any regrets or would like to apologize for the fiasco in Bell.”

State Controller Chiang says that over the years, the city’s auditing firm Mayer Hoffman McCann has done little more than rubber stamp the books, failing to spot red flags and other problems.

Hallye Jordan, Chiang’s spokeswoman, said state auditors are baffled how a CPA firm could miss problems the state found “rather quickly.”

At first, there is dancing and singing, then reality sets in. With four council members arrested, who will govern the city?

Artiga resigns. And minutes before the next meeting, Mayor Oscar Hernandez and Councilwoman Teresa Jacobo call in sick, leaving the council without a quorum.

Lorenzo Velez — the only council member not under criminal investigation — sits alone at the dais, facing the angry crowd.

One by one, six current and former council members are hauled away in handcuffs – as are Spaccia and Rizzo (right), the man many view as the ringleader.

Dist. Atty. Cooley describes Bell as “corruption on steroids.” He charges the “Bell 8” with looting more than $5.5 million in public funds.

The night before his arrest, Councilman Luis Artiga says of his high salary: “I thought God had answered my prayers but it was a trap from the devil.”

State Controller John Chiang (right) finds three instances of illegally collected taxes and orders the city to refund $5.6 million to taxpayers.

Chiang says Bell illegally hiked business license taxes by more than 50% over the last decade. Chiang’s auditors also find that Bell has illegally raised a “retirement tax” to fund pensions, costing taxpayers $2.9 million, and assessed improper sewer fees of more than $600,000.

“It’s like the city wants us to close,” Alberto Alvarado, owner of Nuevo Mundo Super Market, says of the excessive fees.

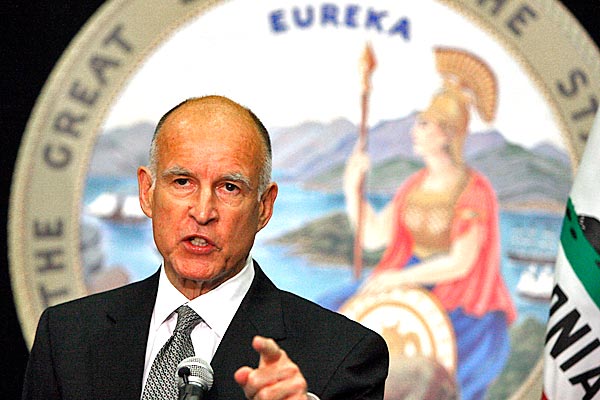

State Atty. Gen. Jerry Brown (right) files a lawsuit accusing eight current and former city officials of concealing their lucrative compensation and plotting to enrich themselves.

Rizzo’s attorney accuses Brown, who is in a close race for governor, of political grandstanding. Brown acknowledges that the lawsuit is highly unusual but says: “We’re testing the proposition of what public officials can pay themselves…. The fact that someone is elected doesn’t mean they get a license to steal, doesn’t mean they get a license to line their pockets.”

Whether it is for property taxes or parking, Bell residents complain about how often they have to open their checkbooks.

In the 2009-10, Bell counts on making $770,000 in towing fees.

Bell Police officers say that top brass instituted what amounts to a daily quota. “Rather than being police officers and being proactive looking for crime, we were out there looking for vehicles to impound,” says police Sgt. Art Jimenez.

The U.S. Justice Department says it will investigate the city’s unusual towing practices for possible civil rights violations.

“Basta!” – “enough” in Spanish — becomes the rallying cry for residents. BASTA, Bell Assn. to Stop the Abuse, gathers 16,000 signatures in an effort to force a City Council recall election.

“We want to ensure that the abuses we suffered from these dishonest so-called leaders can never happen again,” Bell resident Marcos Olivas says.

Bell insiders say that as his tenure in the city lengthened, Rizzo took to quoting tough-guy lines from “The Sopranos” and tolerated no challenges to his expanding authority at City Hall.

“He likes to be in control,” says former Councilman Victor Bello.

Part of that control plays out in loans he doles out without City Council approval. The loans go to him, to council members and nearly 50 of other city employees.

For weeks, Bell refuses to turn over public records to The Times, community activists and even a sitting councilmember.

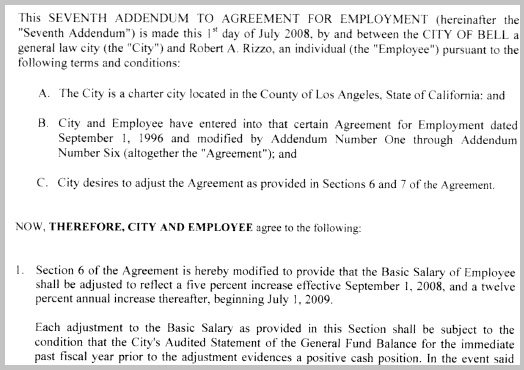

When the city finally starts handing over documents, they show that Rizzo’s true annual compensation is $1.5 million, more than twice what he has claimed.

The documents show that he cashed out 107 vacation days and 36 sick days a year. The city also pays more than $70,000 into Rizzo’s deferred compensation and retirement plans.

“This is extraordinary, it is outlandish,” says Dave Mora, West Coast regional director of the International City/County Management Assn.

How does Rizzo’s pay compare? A Times analysis of city manager compensation in Los Angeles County finds the average pay is about $209,000.

But determining full compensation proves complicated, with benefits and other perks often adding up to more than the publicly-recorded base salaries.

The state controller’s office soon starts requiring cities to report salary, pension benefits and other compensation and, in October, launches a public database.

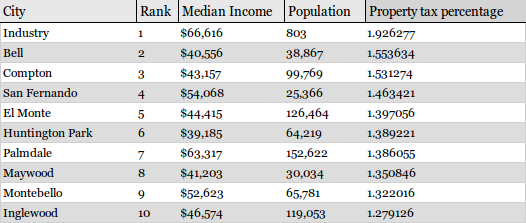

How could Bell, a small, working-class city, afford to pay exorbitant salaries without going bankrupt?

The Times reviews county tax records and finds that Bell residents pay the second-highest property tax rate in Los Angeles County, a finding later confirmed by Controller Chiang.

“They’re robbing us of our money,” said Juan Madrid, 64, who has owned his tidy yellow home in Bell for about 30 years.

Authorities and government agencies turn up the heat on Bell. In addition to Atty. Gen. Jerry Brown’s probe of the city, Los Angeles County Dist. Atty. Steve Cooley (right) launches a wide-ranging investigation into allegations of voter fraud and conflicts of interest. Cooley describes the effort as “multifaceted, rapidly expanding and full-fledged.”

State Controller John Chiang announces that his office will audit the city’s finances. He describes city salaries and pensions as “unjustifiable” and vows to take “a hard look at the books.”

All three officials – Brown, Cooley and Chiang – are running for election to state office.

Before an angry crowd at a packed meeting, Bell City Council members unanimously agree to a 90% pay cut – putting their salaries on par with the pay of the fifth and newest member, Lorenzo Velez, who earns $673 a month.

Hernandez, the mayor, apologizes for the high salaries, a reversal from the defiant tone he struck the week before.

So if the City Council is earning $100,000, how much are top administrators being paid?

Rizzo tells The Times he’s earning $700,000. A review of Rizzo’s contracts shows that he actually makes $787,637 annually. Assistant City Administrator Angela Spaccia makes $376,288 and Police Chief Randy Adams earns $457,000.

When the news hits the front page under the eye-catching headline “Is a city manager worth $800,000?” it sparks widespread outrage.

Bell is facing problems of its own.

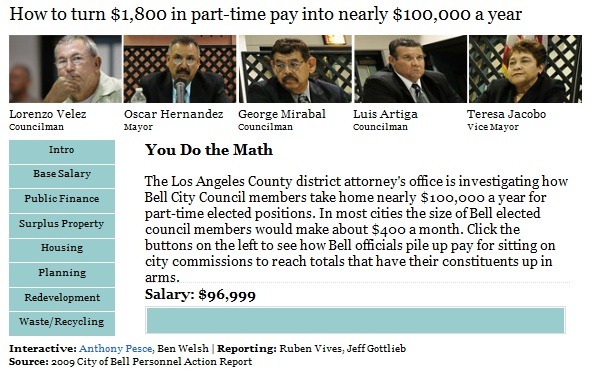

The Times learns that the Los Angeles County district attorney’s office is inquiring into why Bell council members are paid nearly $100,000 a year for a part-time jobs.

Mayor Oscar Hernandez defends their pay: “In a troubled city, the city council should get paid a little more.”

Officials in Maywood — which neighbors Bell — announce plans to lay off nearly all city employees and disband the Police Department. City services will be turned over to Bell.

The move comes after Maywood loses its insurance. “We want to help our neighbor,” Bell Mayor Oscar Hernandez tells The Times. But the arrangement leads to questions: Is Bell the right city to fix Maywood’s problems?

Rizzo is arrested for drunk driving after crashing into a neighbor’s mailbox in his upscale Huntington Beach neighborhood.

Police says Rizzo’s blood-alcohol level is tested at 0.28%, more than three times the legal limit.

Rizzo later pleads guilty and agrees to perform community service. “He’s taken steps to better himself, and he’s moved on,” says his attorney Katherine McBroom.

Bell Councilman Victor Bello abruptly steps down and takes a full-time job running the city’s food bank.

He continues to draw the $96,000-a-year salary he earned as a council member.

Bello’s replacement, Lorenzo Velez (right), doesn’t fare as well. The newly appointed councilman gets only $673 a month and is unaware that his colleagues are making so much. “I was under the impression that I was being paid just like everyone else,” Velez says later.

In emails between assistant city administrator Angela Spaccia and Randy Adams, soon to be hired as police chief, Adams writes, “I am looking forward to seeing you and taking all of Bell’s money?!”

Spaccia responds: “We will all get fat together … Bob has an expression he likes to use on occasion,” she continues, referring to Rizzo. “Pigs get Fat … Hogs get slaughtered!!!! So as long as we’re not Hogs … All is well!”

The emails later become public.

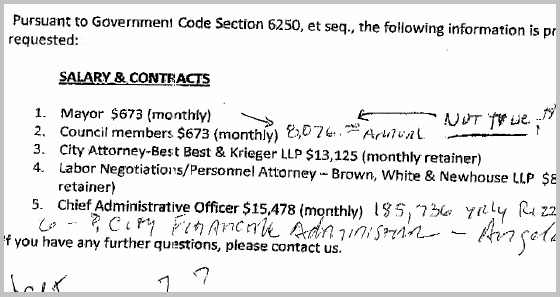

With rumors swirling about exorbitant salaries for Rizzo and other city officials, Bell resident Roger Ramirez files a public record request.

The city responds to his request but vastly low-balls the true payouts.

Without approval from the City Council, Rizzo lends $300,000 of the city’s money to a local Chevrolet dealer, one of the city’s last big tax generators.

There’s no public notice or discussion of the deal and the loan is made directly to car dealer Randy C. Sopp.

When the deal becomes public two years later, several experts say the secret loan violates basic tenets of municipal government and appears to violate Bell’s charter, which requires that all contracts be approved by the City Council.

Bell readjusts property taxes, leaving residents paying the second-highest tax rate in Los Angeles County, largely because of a special “retirement tax” in the city and hefty bond debt.

The city’s tax formula means that the owner of a home in Bell with an assessed value of $400,000 pays about $6,200 in annual property taxes. The owner of the same house in Malibu, whose rate is 1.10%, would pay $4,400.

The city buys a piece of land for more than double its assessed value as part of a highly unusual redevelopment deal that requires seller Albert Neesan (right) to donate $425,000 to the city. That money later cannot be accounted for, according to records and interviews.

Experts later call it a real estate deal run amok. “Essentially they cooked the books on this,” says Larry Kosmont, a Los Angeles real estate consultant and former city manager and director of community development for Burbank, Santa Monica and Bell Gardens.

Council members’ salaries start to jump after Bell becomes a charter city, soaring to $96,996 in 2010. Had Bell remained a general law city, state law would have cemented council salaries at about $400 a month.

On paper, it appears the part time council members are making only $150 a meeting, similar to what most of their counterparts around the state are paid. Most of their money — nearly $8,000 a month — comes from various boards and commissions.

Agendas show that many of those agencies rarely meet. When they do convene, meetings often wrap up in just a few minutes.

In many ways, the Bell scandal starts with a little-noticed special election that turns Bell into a charter city.

Fewer than 400 voters turn out. Only 54 people cast ballots in opposition. The measure itself gives no hint what is at stake.

Because Bell becomes a charter city, its council members are exempt from a new state law that would otherwise limit their salaries. The election essentially opens Bell’s wallet to Rizzo (right) and a few others.

Business owners say the city arbitrarily requires them to make payments and in at least one case threatens to shut down a business for failure to comply.

City records show that one tire shop owner pays at least $144,000 over a four-year period. Another tire shop owner is required to pay $13,000 a year.

Car wash owner Gerardo Quiroz (right) is so outraged at paying his $300-a-month fee that he writes “bribe” in Spanish on the memo line of some of his checks to the city.

Trailing a whiff of scandal, Rizzo is hired in Bell after agreeing to take the city’s top administrative job for $78,000, $7,000 less than his predecessor.

“He was willing to work for the least amount of money,” then Councilman Rolf Janssen recalls years later. “That was what attracted me and several other council members.”

Rizzo helps get the small town back on stable footing and as the town’s fortunes improve, so do Rizzo’s.

Hesperia city leaders sour on Rizzo, whose pay has climbed to at least $95,000 a year, suspecting him of funneling city improvement funds to staff salary increases. The local newspaper reports that Rizzo might have abused his city-issued credit card.

He leaves after signing an agreement that pays him more than $108,000 over nine months for consulting services and requires him, his wife and the City Council to keep the terms confidential, according city records later obtained by The Times.

The desert town of Hesperia incorporates and Robert Rizzo becomes the town’s first city manager, earning a salary of $76,000. Rizzo drums up new revenue and flips pancakes at city functions.

“None of us had ever started a city before, and he seemed to know what he was talking about,” Councilman Howard Roth recalls.

Sources: Times research

Credits: The Los Angeles Times, TimelineSetter