State of the Union: 15 historic moments

Charles Dharapak / Associated Press

Charles Dharapak / Associated Press

Since 1790, the State of the Union has been an annual tradition, a chance for the president to recount the past year’s events, and path the nation should take moving forward. Over the course of hundreds of addresses, these are the moments that stand out the most.

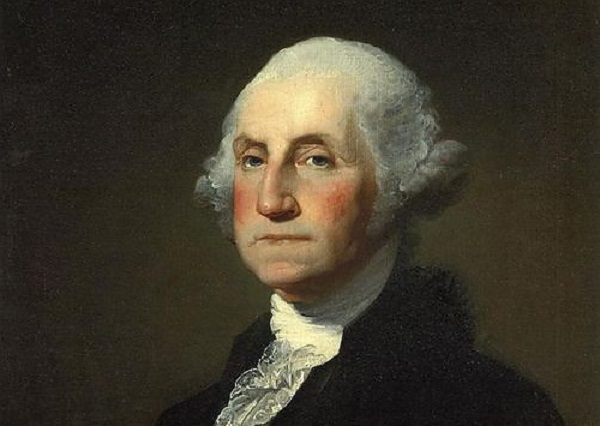

The first State of the Union address

President Washington was, predictably, the first president to deliver an annual address to a joint session of Congress, on Jan. 8 in the provisional capital of the U.S.: New York City.

Washington delivered his address due to a requirement in Article II, Section 3 of the Constitution, which reads:

“He [the president] shall from time to time give to the Congress information of the state of the union, and recommend to their consideration such measures as he shall judge necessary and expedient.”

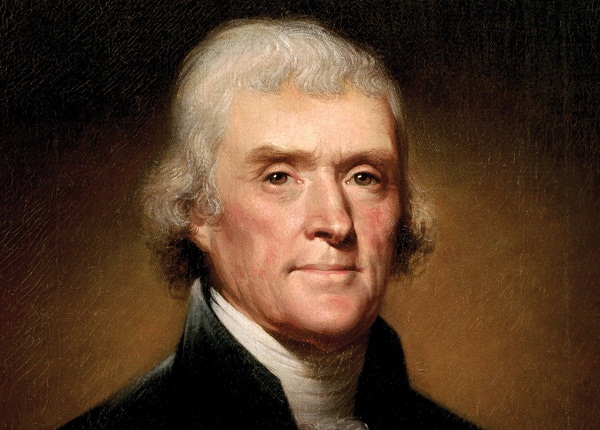

Jefferson changes the address

After Washington’s first address, the State of the Union was delivered to Congress verbally until 1801, when President Jefferson decided that the act of the president standing before Congress and delivering the address was too similar to British customs.

Jefferson wrote the address, which was given to a clerk, who then delivered the speech to Congress. Jefferson’s refusal to personally give the speech to Congress set the precedent for over 100 years.

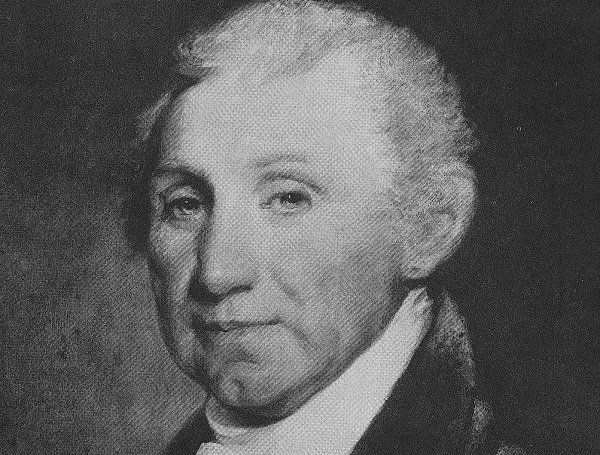

Monroe doctrine declared

President Monroe first introduced the doctrine that bears his name during his seventh State of the Union address. In his speech, Monroe made it U.S. policy to treat any new European incursions into North or South America as hostile acts. Established colonies and Europe’s own political affairs, Monroe said, were to be left alone as part of the new doctrine.

“It is only when our rights are invaded or seriously menaced that we resent injuries or make preparation for our defense. With the movements in this hemisphere we are of necessity more immediately connected, and by causes which must be obvious to all enlightened and impartial observers,” Monroe said, setting a foreign policy precedent that presidents would cite for decades.

California Gold Rush confirmed

President James K. Polk’s 1848 State of the Union address confirmed reports “of the abundance of gold” in California. Until his address, many Americans were reluctant to believe the news of gold since false reports had been made in the past.

In the address, Polk urged Congress to create a branch of the United States mint in California to “more speedily and fully avail ourselves of the undeveloped wealth of these mines.”

As part of the treaty ending the Mexican-American War, the U.S. took ownership of California in 1848. After Polk’s announcement, an exodus of “forty-niners” poured into the region and in 1850, less than two years later, California became the 31st state.

The president returns to Congress

For decades, the State of the Union address was delivered to Congress and read by a clerk, a far cry from the address today, which is delivered by the president and viewed by millions. In 1913, President Wilson broke from the tradition started by Jefferson and delivered his remarks directly to Congress.

FDR’s ‘Four Freedoms’

President Franklin D. Roosevelt used his 1941 State of the Union address to outline “four essential human freedoms” that the United States should seek to protect. As World War II ravaged Europe, Roosevelt said freedoms of speech and religion as well as the freedom from want and fear should extend to people “everywhere.”

“That is no vision of a distant millennium,” he said after outlining the four principles. “It is a definite basis for a kind of world attainable in our own time and generation. That kind of world is the very antithesis of the so-called new order of tyranny which the dictators seek to create with the crash of a bomb.”

Roosevelt used the speech, criticized by isolationists, to argue for continued aid to the United Kingdom. The address was delivered on Jan. 641. By the end of the year, the United States would be at war.

The first televised address

The first State of the Union address to be televised across the country began with a joke.

“Mr. President, Mr. Speaker, members of the Congress of the United States. It looks like a good many of you have moved over to the left since I was last here,” President Harry S. Truman said, joking about the increased Republican presence seated to his left after the 1946 elections.

Truman then shifted his attention to the typical plethora of policy proposals, from protection for labor reforms, a united front in international affairs, progress on civil rights and a reduction of the military’s size.

The ‘War on Poverty’

At the opening on President Lyndon B. Johnson’s inaugural State of the Union address, delivered just months after President Kennedy’s assassination, Johnson laid out a sweeping vision for the upcoming session of Congress.

“Let this session of Congress be known as the session which did more for civil rights than the last hundred sessions combined; as the session which enacted the most far-reaching tax cut of our time; as the session which declared all-out war on human poverty and unemployment in these United States; as the session which finally recognized the health needs of all our older citizens,” Johnson said, continuing to list on further areas of reform.

The phrase “all-out war on human poverty” was quickly simplified into the “war on poverty,” and became a centerpiece of Johnson’s presidency. Congress passed the Economic Opportunity Act soon after, which funneled federal money through the Office of Economic Opportunity to combat poverty.

At the time, the national poverty rate was near 19%. In two years, the poverty rate dropped to around 15%, a figure just one point less than the most recent poverty rate calculated by the Census Bureau.

First opposition party response

For a tradition that’s proliferated greatly in recent years, the opposition response is a relatively new invention. It wasn’t until 1966 – President Lyndon B. Johnson’s third year as president – that an opposition party offered a rebuttal to the State of the Union.

Delivered by Senate Minority Leader Everett Dirksen (R-Ill.) and then-House Minority Leader Gerald Ford (R-Mich.) in the old Senate Chamber, the response came five days after the president gave his State of the Union speech. The joint rebuttal was taped and picked up on several networks.

Though most responses in recent years feature one member of the opposition party speaking into a camera, past responses have embraced a variety of formats. The Democrats’ 1982 response, for example, took the form of a prerecorded 28-minute special aired on major networks. It featured key party names of the time, including California Gov. Jerry Brown, Sen. Edward M. Kennedy (D-Mass.) and Rep. Al Gore (D-Tenn.).

‘One year of Watergate is enough’

Leading an administration embroiled by Watergate, President Nixon called for ending investigations into the scandal would ultimately cut short his presidency.

“One year of Watergate is enough,” he proclaimed at the end of a 1974 speech largely centered on the energy crisis and his first-term achievements.

Despite his statement, Nixon said he would cooperate with the House Judiciary Committee’s investigation, but would not do anything that might weaken the decision-making process for future presidents. In the months leading up to the speech, the White House had fallen under scrutiny for not fully cooperating with investigations into whether it covered up the 1972 break-in at Democratic National Committee headquarters.

“I want you to know that I have no intention whatever of ever walking away from the job that the people elected me to do for the people of the United States,” Nixon said during the final moments of his speech.

But in late July, the Supreme Court ordered the president to turn over White House tapes and the House Judiciary Committee passed three articles of impeachment. Nixon resigned on Aug. 8.

Reagan delays his address

President Reagan is the only president to have delayed a State of the Union address. Scheduled for Jan. 28, Reagan pushed the speech off until Feb. 4 after the space shuttle Challenger exploded 73 seconds after liftoff, killing all seven crew members on the day he was to deliver the address.

Reagan opened his address with a tribute to the fallen astronauts.

“Thank you for allowing me to delay my address until this evening. We paused together to mourn and honor the valor of our seven Challenger heroes. And I hope that we are now ready to do what they would want us to do: Go forward, America, and reach for the stars. We will never forget those brave seven, but we shall go forward,” he said.

The ‘era of big government is over’

On the heels of two federal shutdowns, President Clinton created a stir during his 1996 speech when he said the “era of big government is over.” Clinton also placed an often-forgotten caveat on this declaration: that government is not irrelevant.

“But we cannot go back to the time when our citizens were left to fend for themselves,” he cautioned after the “era of big government” line, adding that “self-reliance and teamwork are not opposing virtues.”

The speech followed the 1994 midterm elections, during which the GOP, campaigning on a smaller government platform, won majorities in both chambers of Congress for the first time in 40 years. Clinton saw a bump in his approval rating after his 1996 State of the Union and even won a tepid acknowledgment in the GOP’s rebuttal.

“…while the president’s words speak of change, his deeds are a contradiction,” Senate Majority Leader Bob Dole (R-Kan.) said in the party’s response. “The president claims to embrace the future while clinging to the policies of the past.”

The ‘Axis of Evil’

President George W. Bush, in his first State of the Union address following the Sept. 11 attacks, strongly condemned North Korea, Iran and Iraq after applauding American military action in Afghanistan against the Taliban and Al Qaeda.

“States like these and their terrorist allies constitute an axis of evil, arming to threaten the peace of the world,” he said, drawing a rhetorical connection to the Axis powers of Italy, Germany and Japan, that the U.S. fought during the World War II.

And to the new “Axis” nations, Bush issued a clear warning.

“We will work closely with our coalition to deny terrorists and their state sponsors the materials, technology, and expertise to make and deliver weapons of mass destruction. We will develop and deploy effective missile defenses to protect America and our allies from sudden attack,” Bush continued. “And all nations should know: America will do what is necessary to ensure our nation’s security.”

Obama addresses Citizens United

One week after the Supreme Court weakened campaign finance restrictions on corporations, nonprofits and unions, its justices found themselves occupying their customary front-row seats at President Obama’s 2010 State of the Union address. But neither that nor separation of powers stopped Obama from delivering a harsh critique of the court’s ruling in Citizens United vs. FEC.

“With all due deference to separation of powers, last week the Supreme Court reversed a century of law to open the floodgates for special interests — including foreign corporations — to spend without limit in our elections,” Obama said, urging Congress to pass new campaign finance legislation.

Obama received a standing ovation from some members of the audience. But the justices sat silently in their seats, unmoved, with the exception of Justice Samuel Alito, who was spotted mouthing, “That’s not true.”

Chief Justice John Roberts addressed the incident later that year, saying “The image of having the members of one branch of government standing up, literally surrounding the Supreme Court, cheering and hollering while the court, according to the requirements of protocol, has to sit there expressionless, I think, is very troubling.”

First tea party response

After the tea party helped the GOP secure a majority in the House of Representatives during the 2010 midterm elections, one of the movement’s largest groups broadcast its own State of the Union response. With Rep. Michele Bachmann (R-Minn.) as its messenger, the Tea Party Express called for Obamacare’s repeal and a balanced budget amendment.

Bachmann, who created the Tea Party Caucus, said President Obama ignored pleas to curb spending.

“Instead of cutting, we saw an unprecedented explosion of government spending and debt at President Obama’s direction,” she said.

In 2012, former Republican presidential candidate and pizza executive Herman Cain delivered the tea party’s response. Last year, the task fell upon Sen. Rand Paul (R-Ky.) and this year, Sen. Mike Lee (R-Utah) will speak for the organization.

Sources: Los Angeles Times research

Credits: By Morgan Little and Daniel Rothberg, TimelineSetter